Reading from Left to Left: Radical Bookstores in NYC, 1930-2000s

By Shannon O’Neill

The text of this post primarily comes from the labels and zine accompanying the exhibition Reading from Left to Left: Radical Bookstores in NYC, 1930-2000s, curated by Shannon O’Neill. The show drew on collection material from the Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, the Fales Library & Special Collections, and the New York University Archives at NYU Special Collections. Not every bookstore represented in the exhibition is discussed in this post.

In the early morning of July 22, 1968, right-wing extremists bombed the Communist Party’s Jefferson Bookshop. [1] The bombing, while shocking, was not a surprise; Jefferson Bookshop had been singled out for years. Its windows, which hosted displays against the war in Vietnam, had been smashed more than once. What is so threatening about a bookstore that its opponents would want to destroy it?

Jefferson Bookshop doorway post-bombing, Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, NYU Special Collections, PHOTOS.223.001, Box 13c, Shoot 680216.

The people of New York have always risen up to fight against oppression. Throughout decades of labor strikes, student uprisings, building occupations, mass direct action and protest, radical bookstores have created spaces where activists could meet, learn, teach, share, rest, and recreate with one another. Radical bookstores and bookstore workers have always nurtured rebellion. More than simply being sites of political participation and exchange, radical bookstores serve as critical infrastructure within New York City’s social movement landscape. They are, and have always been, key to building and informing resistance movements. This, perhaps, is why they pose such a threat.

Radical Bookstores and Party Politics

As pivotal spaces for leftists to strategize and engage one another, political party bookstores were key in supporting the labor movement, pushing for racial equality, working on behalf of revolutionary freedom fighters, and participating in global solidarity and struggle. In doing so, they created the space for their customers to not only radically reimagine their worlds, but to participate in activating their radical imaginations.

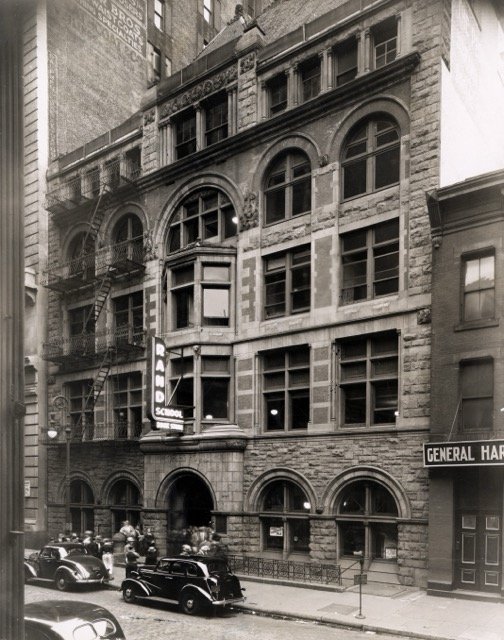

The Social Party of America’s Rand School of Social Science began in 1906 as a project to build class-consciousness and political education amongst workers. In 1917, the Rand School moved to 7 E.15th Street, calling its new building the “People’s House” and offering social spaces like an auditorium for events, a restaurant, and a bookstore.

Rand School exterior, Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, NYU Special Collections PHOTOS.001, Box 5, Folder 363.

The bookstore was lauded as the largest in the city. In 1919, it was raided by the Lusk Committee — a post-World War I committee formed by the New York State Legislature to investigate individuals and organizations that the government suspected of sedition. The Rand School Bookstore survived the Lusk Committee and grew to be a key player in New York City’s publishing world – exchanging business Random House, Knopf, MacMillan, Little Brown, and Barnes & Noble. In an ironic turn, Barnes & Noble became one of the corporate forces that pushed many independent and radical bookstores out of the city in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

The Rand School Bookstore’s focus and significance lay in its support for the labor movement. Unions across the country contacted the Rand School Bookstore to supply them with books and pamphlets for their members. In spite of its popularity, the Rand School bookstore struggled through the onslaught of post-World War I right-wing attacks on Socialism. Records show that, by the 1930s, the store was working off of credit and the goodwill of publishers and movement workers across the city. In 1933, the People’s House launched a campaign to keep its doors open. They prevailed for a time, but by the late 1940s, the vast majority of the bookstore’s inventory was liquidated and in 1956, as anti-radical fervent swept across the country, the Rand School of Social Science and its bookstore shuttered entirely.

In 1927, the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA) moved its headquarters from Chicago to New York City. By the early 1940s, CPUSA was operating several storefront bookshops including Workers Bookstore, Progressive Bookshop, the Jefferson Bookshop, and Unity Book Center. Workers Bookstore and Progressive Bookshop were Communist franchises, so to speak, with locations across the United States. The Jefferson Bookshop and Unity Book Center, however, remained unique to New York City. [4]

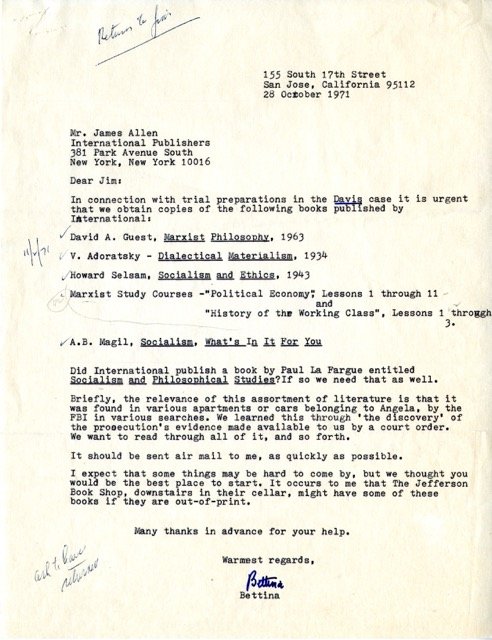

The Jefferson Bookshop was a part of the Jefferson School–once the flagship educational institution for the CPUSA. In 1972, activist, philosopher, author, and academic, Angela Davis was brought to trial on charges of kidnapping, murder, and conspiracy. Activist, author, and later professor Bettina Aptheker was a part of Davis’ defense committee. Knowing that the prosecution was utilizing Davis’ library as evidence in her trial, Aptheker turned to the Jefferson Bookshop to request copies of books in the store’s cellar. It is unknown whether the Bookshop ultimately supplied these texts to the defense; however, the nature of the letter illuminates the relationship between the bookstore, the Communist Party, and the struggle for Black Liberation.

Jefferson Bookshop Bettina Aptheker support for Angela Davis, Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, NYU Special Collections, TAM.132, Box 92, Folder 12.

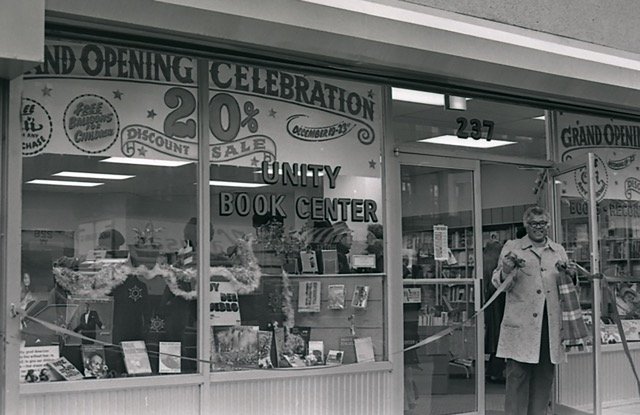

When the Jefferson Bookshop closed, the Communists tried to build one last bookstore in New York City with the Unity Book Center, which opened in December of 1978. Unity Book Center envisioned itself as more than a bookstore. In a proposal for the Unity Book Center, its workers instruct, "the bookstore must be the most open, sensitive, and caring institution.” [5] Unity aimed to function as a community resource, with early access to computers that helped connect workers to a changing labor force. The political upheaval of the 1980s and general disintegration of state socialism deeply impacted CPUSA’s bookstore operations, and, eventually, the Unity Book Center closed its doors as well.

Unity Bookstore Grand Opening, Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, NYU Special Collections, PHOTOS.223.001, Box 22d, Shoot 780106.

Radical Bookstores and Counterculture

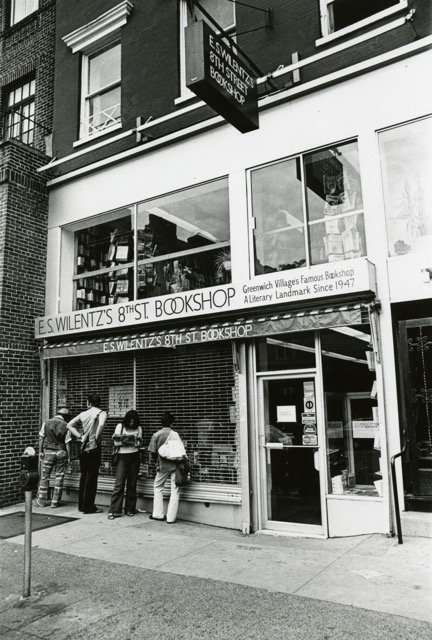

New York City is an epicenter for counterculture and radical bookstores have always been a part of the city’s countercultural movements. For decades, the Eighth Street Bookstore was a literary gathering place for the nonconformist writers and poets who would come to be known as the Beat Generation. The store, opened and run by Ted and Eli Wilentz from 1947 to 1979, embraced the paperback phenomenon of the 1940s, and specialized in Beat writers. Eli Wilentz edited the first collection of writing dedicated to the movement called The Beat Scene. Beat Writers like Peter Orlofsky worked at the shop, and Allen Ginsberg lived in a room above the store after returning to the United States from India in 1964. [6]

8th Street exterior, New York University Archives, NYU Special Collections, PHOTO.00001, Box 176, Folder “Washington Square Area East 8th Street.”

While Ginsberg was living in India he received a package from Ed Sanders–an activist, Yippie, and co-founder of the band the Fugs. Sanders received Gingberg’s address from one of the Wilentz brothers at the Eighth Street Bookstore and mailed a copy of his magazine Fuck You / A Magazine of the Arts. In 1964, Sanders formed Peace Eye Bookstore. The store–from which his mimeograph machine churned out copies of Fuck You, the Marijuana Newsletter, and other titles–quickly became a hangout for downtown radicals, and hosted art shows like the first exhibition of underground comics by R. Crumb and Art Spiegelman. In January of 1966, police raided Peace Eye, confiscating Sanders’ inventory and charging him with possession of obscene literature with intent to sell. Sanders eventually fended off the charges with support from the ACLU after a year-long court battle. [7]

Before the Wilentz brothers and Sanders, Frances “Fanny” Steloff ran the Gotham Book Mart. Like the Wilentz’s, Fanny’s Gotham employed Beat writers, and, like Sanders, Fanny went up against the law. For decades, Steloff was harassed by the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV). The NYSSV was deputized by the New York State Legislature to seize literature it deemed “immoral,” and it was authorized to arrest those that the NYSSV found in violation of obscenity laws. Steloff, an active opponent to government censorship, famously smuggled books like James Joyce’s’ Ulysses into the United States. In 1946, she refused to remove a display in Gotham’s window, created by Marcel Duchamp and André Breton, that the NYSSV called obscene. Instead, Fanny covered parts of the display with an NYSSV business card, across which she scrawled “censored.” [8]

By the 1980s, the subversive legacy of New York City — particularly the history of neighborhoods like the Lower East Side where Peace Eye once prospered — became cultural capital for developers to harness. As the Giuliani administration purged the city of so-called deviance, counterculture was co-opted and defanged. The once wild allure of the city became a brand that real estate developers use to attract new, middle, and upper-class residents. The Yippie was pushed aside for the yuppie, and countercultural bookstores faded into the background.

Radical Bookstores and Autonomous Space

Radical bookstores are an expression of activist placemaking–they are formed because activists demand and create autonomous spaces. For many bookstores, one way a political community is formed is through their bookshelves’ curation. The shelf, reflecting booksellers’ worldview, becomes a material component of political action. In this way, Black, feminist, queer, and anarchist bookstores, and sidewalk booksellers, become more than sites for the exchange of goods and money; they claim space, and in doing so, they are world-building–a foundational principle in radical politics. We see this reclamation of space in the upending of corporate business models, the breaking away from the constraints of party politics, the embracing of DIY (do-it-yourself) ethics and practices, and–at times–quite literally taking space as their own.

Anarchist stores like Blackout and Mayday pushed against hierarchical labor structures by forming themselves as all-volunteer. Blackout began as a sidewalk-vending and punk show-tabling project before securing a storefront. As a volunteer organization, Blackout workers created a zine-like manual to guide their everyday work. [9] This manual included opening procedure instructions to purchase a cup of coffee from "the cute Arab kid at the bodega at the southeast corner of Avenue B." Blackout Books circulated a monthly calendar of events that, in keeping with the store's stated principle of "working toward a society based on mutual cooperation," amplified events of multiple allied organizations across the city—from a rally to support fired transit worker Roger Toussaint (who later went on to lead the three-day-long 2005 MTA strike)—to a Palestinian dance and poetry performance. Blackout Books eventually lost its space when its landlord hiked the storefront's rent up by 50%. [10]

Following the closure of Blackout Books, May Day opened inside the entrance to the Theater for The New City. Like its predecessors, May Day was more than just a purveyor of books. It was a gathering space for sharing information about local, national, and international politics. In the early 2000s, collective members of May Day planned the Intergalactic Anarchist Convention, a four-day event leading up to protests around the World Economic Forum in New York City.

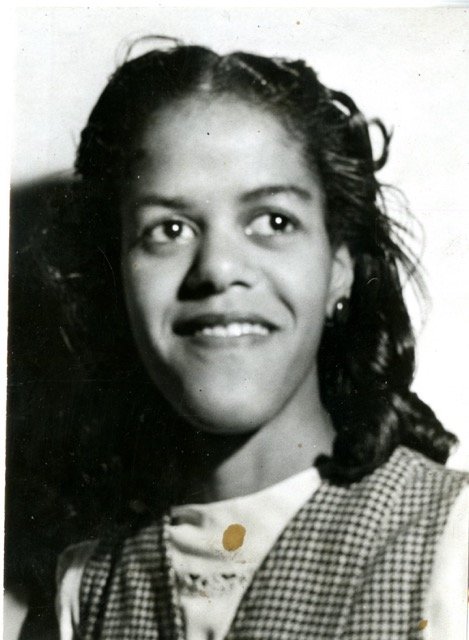

While some radical bookstores rejected capitalist profit motives, others attempted to harness the marketplace as a way to introduce the masses to radical ideas and to create economic independence from violently racist systems. Black-owned bookstores like Una Mulzac’s Liberation promoted Black power, Black nationalism, pan-Africanism, and anticolonialism. Una Mulzac was a life-long radical and bookseller. In the 1960s, Mulzac left the United States and joined the anti-colonial People's Progressive Party (PPP) in Guyana. As a member of the PPP she ran the party's bookstore which — similar to the Jefferson Bookshop — was bombed, severely wounding Mulzac. After recovering, Mulzac moved to Harlem and opened Liberation Bookstore. Originally, the store was an information center for the Progressive Labor Party (PLP). By 1969, Mulzac was disenchanted with the PLP and focused Liberation's inventory on Pan-Africanism and anti-colonial texts. For another thirty-plus years Liberation was a central space for research and education. In 2000, Liberation faced eviction; however, Mulzac and the bookstore received widespread support and the store remained open for seven more years. [11]

Una Mulzac Portrait, Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, NYU Special Collections, PHOTOS.223, Box 216, Folder 12462a.

Gay and feminist bookstores like Craig Rodwell’s Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop and IKON Magazine’s IKON bookstore were critical spaces to the LGBTQ and women’s liberation movements. Craig Rodwell was no stranger to activism. He started the Homophile Youth Movement Neighborhood (HYMN), and he was involved in numerous pickets of homophobic institutions in the 1960s. Following the Stonewall Uprising in 1969, Rodwell co-organized the first gay pride march held in New York City. After working multiple summers on the Fire Island Boatel, Craig Rodwell saved enough money to rent a storefront in the West Village. He called his new store the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop, and he filled the store with books, pamphlets, and buttons. [12]

In May of 1968, Susan Sherman, a founding editor of IKON magazine, opened IKONstore. The store became an important resource to its surrounding community. Residents of 4th Street held block meetings in the storefront, forming one of the city's first block associations, and the store’s workers designed and printed weekly programs for the La MaMa Experimental Theatre (in exchange, for which, La MaMa founder Ellen Stewart paid IKONstore’s $125 monthly rent). [13]

Critically, IKONstore was also a resource to activists. On New Year’s Eve, 1970, two hundred women squatted at 330 E. 5th St. Susan Sherman was one of the first women in the building. The women held the building for nearly two weeks, transforming it into a women’s center where they offered free child care, a food co-op, a book and clothes exchange, and a feminist school. On January 14th, 1971, police violently arrested 24 women, forcing the end of the 5th Street Women's Building takeover. The building was soon thereafter demolished and turned into a parking lot for the local police precinct. [14]

Flyer from 5th Street Women’s Building in exile from IKON bookstore, Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, NYU Special Collections, TAM.356, Box 5, Folder 49.

Sidewalk booksellers have long pushed the boundaries of what a bookstore can be, and who can be defined as a bookseller. Fighting against nimbyism, Mayor Giuliani’s “quality of life” crusade, discriminatory policing, and racial profiling, sidewalk booksellers challenged normative perceptions of the marketplace and pushed back against city policy in order to gain their right to sell books on the street.

In the 1970s and 1980s, David Ferguson sold his literary magazine Box 749 on Manhattan’s sidewalks. He was routinely harassed and arrested by the police for selling without a vendor's license. In 1982, with help from New York Civil Liberties Union lawyer Arthur Eisenberg, Ferguson lobbied City Council to amend the General Vending Statute allowing for the "sale of newspapers, periodicals, or other written matter without the use of a pushcart, stand, booth, or vehicle." This exempted "vendors of written material" from city laws prohibiting individuals from selling goods on the street without a license. The amendment was ultimately signed by Mayor Edward Koch, which revised the city code and paved the way for sidewalk sellers to come. [15]

Cover of Box 749, Volume 1, Fales Library, NYU Special Collections, Fales Books Box 749.

Radical Bookstores, Gentrification, & Fighting Back

It is somewhat easy to imagine the era of the radical bookstore as a “bygone” one. By the 1980s—fueled by “broken-windows'' policing; rezoning that prioritized highways over thriving city centers; and tax exemptions benefiting the wealthy-–New York City real estate began its steady climb toward inaccessibility. This market, which favored entrepreneurs, professionals, and big box stores like Borders, was devastating to small businesses like radical bookstores.

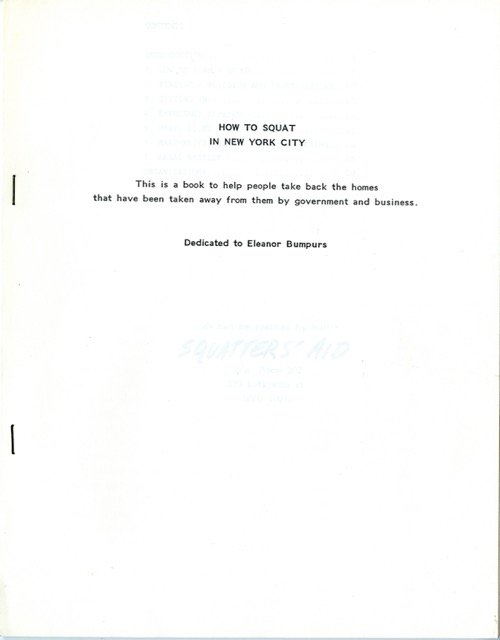

In spite of this, New Yorkers have never accepted gentrification as an inevitability and have always found creative ways to resist: they transform abandoned property into livable homes and thriving gardens, they go on rent strike, hold solidarity marches, and share information with one another. Much of the knowledge of how to resist—found in simply stapled booklets such as How to Squat in New York City—circulated through radical bookstores. How to Squat was originally published in 1986 and was revised in 1989. The text is dedicated to Eleanor Bumpurs, who was murdered by the NYPD in her home when the police attempted to enforce her eviction.

Cover of How to Squat in New York City pamphlet, Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, NYU Special Collections, TAM.792, Box 5, Folder “Anarchist Publications.”

Perhaps one need not wonder where the radical bookstores have gone; radical bookstore culture has never fully departed the city, and—one could argue—this culture is currently experiencing a re-emergence of sorts. Workers at bookstores like Word Up, Playground Annex, Mil Mundos, The Word is Change, Yu and Me, Cafe con Libros, Bureau of General Services—Queer Division, Sister’s Uptown, Topos, and Bluestockings continue to push what it means to be a community-based, radical bookstore. Many are practicing mutual aid by distributing food and providing community health resources. Workers at chain stores, too, are tapping into radical bookstore culture. In the last two years, workers at Barnes & Noble have started to unionize. Last year, staff at the Union Square Barnes & Noble staged a walkout, and workers at the Upper West Side store filed for union election seeking representation from the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU).

Getting Free

Though radical bookstores are counterspaces for activist placemaking, they are also convergence spaces; they are “contradictory socio-spatial sites where people from different backgrounds and different radical traditions have been forced together and have subsequently produced new articulations of struggle.” [16] As such, radical bookstores are powerful tools in the landscape of resistance. They reveal the necessity of political education, infrastructure for solidarity, and networks of information within social movements

Radical bookstore revolutionary praxis takes many forms as bookstore politics are the politics of everyday resistance. Bookstore radicalism is defined by a collective politics and tendency toward cooperation; a pushing against and a bringing together; countering and converging. Radical bookstores’ everyday-ness makes them essential to maintaining resistance; in some respects, they are its foundation. While this foundation has been tested by forces of gentrification, policing, imperialism, and capitalism, radical booksellers have refused and defied those forces in an effort to move us ever closer to freedom.

For the book people of Gaza: the bookstore owners, publishers, librarians, archivists, poets, authors, and journalists. For Samin Mansour, and his bookshop, and with gratitude to my first radical bookstore, The Wooden Shoe, in Philadelphia.

May we all get free.

Shannon O’Neill is an archivist, curator, and public historian. She is the curator for the Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, NYU Special Collections. Previously she was the Director of the Barnard Archives and Special Collections and worked for the Atlantic City Free Public Library and the Los Angeles Public Library.

[1] Gansberg, Martin, “2 Seized in Plot to Bomb Union Square Bookstore,” New York Times, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1968/02/20/77171955.html?pageNumber=16. Blumenthal, Ralph, “Bookshop Bombed in Union Square,” New York Times, ://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1968/07/22/76953943.html?pageNumber=1.

[2] Rand School of Social Science Records; TAM 007; Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

[3] Clark Davis, Joshua, “The Forgotten World of Communist Bookstores,” Jacobin, August, 2017, https://jacobin.com/2017/08/communist-party-cpusa-bookstore-fbi.

[4] CPUSA Records; TAM.132, Box 188, Folder 5; Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

[5] Digory, Terence, “Eighth Street Bookstore and the New York School Poets,” in Encyclopedia of the New York School Poets, Second edition. Facts on File Library of American Literature. New York: Facts on File, Inc. EbscoHost.

[6] Sanders, Ed, Fug You: An Informal History of the Peace Eye Bookstore, the Fuck You Press, the Fugs, and Counterculture in the Lower East Side, Cambridge, MA : Da Capo Press, 2011, pg. 255.

[7] Rogers, W. G., Wise Men Fish Here: The Story of Frances Steloff and the Gotham Book Mart, Harcourt Brace & World, 1965, pg. 102.

[8] Renaldo, Rachel, “Blackout Bookstore and Info-Shop,” ABC No Rio, ABC No Rio History, http://www.abcnorio.org/about/history/blackout.html.

[9] Hood, Julia, “Lights Out for Blackout Books, City Limits, https://citylimits.org/2000/07/24/lights-out-for-blackout/.

[10] Martin, Douglas, “Una Mulzac, Bookseller with a Passion for Black Politics, Dies at 88, New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/05/nyregion/una-mulzac-harlem-bookseller-with-a-passion-for-black-politics-dies-at-88.html.

[11] Duberman, Martin, Stonewall: The Definitive Story of the LGBTQ Rights Uprising that Changed America, Plume (revised edition), 2019, pg. 162-163.

[12] Sherman, Susan, America’s Child: A Woman’s Journey Through the Radical Sixties, 2007, pg. 178.

[13] Cowan, Liza, “Side Trip: The Fifth Street Women’s Building Takeover: A Feminist Urban Action, January 1971,” Dyke: A Quarterly, https://www.dykeaquarterly.com/side-trip-1971-takeover-of-the-5th-st-womens-building-nyc/#_edn13.

[14] Duneier, Mitchell, Sidewalk, New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1999, pg.134.