Places of Invention: Nikola Tesla's Life in New York

By W. Bernard Carlson

“Tesla in His Laboratory—Portrait Obtained by an Exposure of Two Seconds to the Light of a Single Vacuum Tube . . .—Photographed by Tonnele & Co.” From “Tesla’s Important Advances,” Electrical Review, 20 May 1896, 263.

Leonardo da Vinci’s studio in Milan. Thomas Edison’s laboratory at Menlo Park, New Jersey. Jobs and Wozniak in the family garage in Los Altos, California. Although we tend to think about creativity as an abstract, cerebral process, invention actually takes place in specific locations that inform the design and content of a device. For Nikola Tesla, nearly all of his creative work took place in Manhattan, and where he worked, lived, and played profoundly shaped his inventions.

Tesla was born in 1856 to a Serbian family living in what is today Croatia. While a college student, Tesla became convinced that it should be possible to develop a better electrical motor that employed alternating current instead of direct current. In pursuit of the practical knowledge needed to perfect this invention, Tesla worked for Edison companies in Budapest and Paris. Impressed with his ability as a trouble-shooter for electric lighting systems, Edison managers transferred Tesla to New York.

Tesla landed in New York in June 1884. Having lived in cosmopolitan Budapest and Paris, Tesla was initially shocked by the crudeness of New York. As he wrote in his autobiography,

Broadway looking north from Cortland Street (left) and Maiden Lane (right), circa 1880, just before Tesla landed in New York. From John A. Kowenhoven, The Columbia Historical Portrait of New York: An Essay in Graphic History (New York: Harper & Row, 1972).

What I had left was beautiful, artistic, and fascinating in every way; what I saw here was machined, rough, and unattractive. A burly policeman was twirling his stick which looked to me as big as a log. I approached him politely, with the request to direct me [to an address]. ‘Six blocks down, then to the left,’ he said, with murder in his eyes. ‘Is this America?’ I asked myself in painful surprise. ‘It is a century behind Europe in civilization.’[1]

But Tesla did not dwell on the contrasts between Europe and America, for he was soon busy working at the Edison Machine Works on Goerck Street [today Baruch Place] on the Lower East Side. There, Tesla drew up plans for an arc-lighting system. He also continued to turn over ideas in his mind for an AC motor, but he was cautious about sharing these ideas with Edison. On one occasion, Tesla almost told Edison about his motor. “It was on Coney Island,” he recalled, “and just about as I was going to explain it to him, some one came and shook hands with Edison. That evening, when I came home, I had a fever and my resolve rose up again not to speak freely about it to other people.”[2]

Group of men standing in front of the Edison Machine Works on Goerck Street in New York around the time that Tesla worked there. Tesla is not in the group. From Nikola Tesla, Notebook from the Edison Machine Works (Belgrade: Nikola Tesla Museum, 2003), 11.

Tesla assumed that his arc lighting system would be valuable to the Edison organization and that he would handsomely rewarded for his work. However, when that didn’t happen, Tesla quit in disgust and found new backers in Rahway, New Jersey who helped him to patent and build his own arc-lighting system. However, once the Rahway businessmen had a lighting system up and running, they fired Tesla. Destitute, Tesla returned to New York to dig ditches.

Fortunately, Tesla helped dig ditches for the installation of cables connecting the headquarters of the Western Union Telegraph Company with stock and commodity exchanges and he came to the attention of Alfred S. Brown who was supervising the work. Brown took a liking to Tesla and introduced him to Charles Peck, a lawyer who had just made a fortune by forcing Jay Gould to buy his Mutual Union Telegraph Company. Looking for a new high-tech venture, Peck and Brown decided to back Tesla in 1886.

Tesla in 1885. From Smithsonian Institution, Neg. 83-13979.

To set Tesla up, Peck and Brown rented a laboratory at 89 Liberty Street in the financial district. [89 Liberty is across the street from Zucotti Park, the site of Occupy Wall Street in 2011.] On the ground floor was the Globe Stationery & Printing Company, and Tesla occupied a room upstairs, furnished with only a workbench, stove, and a generator. To provide power for the generator, Peck and Brown struck a deal with the printing company. Because Globe used its steam engine to run the presses during the day, the company could provide power at night to Tesla. As a result, Tesla got into the habit of working on his inventions at night.[3] At Liberty Street, Tesla perfected his ac motor, feeding several out-of-phase currents into the motor in order to create a rotating magnetic field. Tesla promptly patented this idea and Peck sold the patents to George Westinghouse.

To put his motor into production, Tesla moved briefly to Pittsburgh to work with the engineers at Westinghouse but he soon returned to Manhattan in 1889. Having learned that the German physicist Heinrich Hertz had detected radio waves, Tesla eagerly rented a new laboratory at 175 Grand Street in what is today Little Italy. There, Tesla perfected a high-voltage, high-frequency transformer that is now commonly called a Tesla coil.

To show how his high-frequency coil could be used for wireless lighting, Tesla lectured at the spring 1891 meeting of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. In a lecture hall at Columbia University, [then at 49th Street between Madison and Fourth Avenues] Tesla offered a breathtaking demonstration. Two large zinc sheets were suspended from the ceiling and connected to a Tesla coil. With the lights dimmed, Tesla took a long gas-filled tube in each hand and stepped between the two sheets. As he waved the slender tubes, they glowed, charged by the electrical field set up between the plates.

Tesla demonstrating his wireless lamps at Columbia University, May 1891. From "Experiments with Alternate Currents of Very High Frequency and Their Application to Methods of Artificial Illumination," Electrical World, 11 July 1891, pp. 18-19.

The Columbia lecture established Tesla as a leading electrical inventor, and he had done so in a few short years after arriving in New York. “At one bound,” exulted Harper’s Weekly, Tesla had “placed himself abreast of such men as Edison, Brush, Elihu Thomson, and Alexander Graham Bell. Yet only four or five years ago, after a period of struggle in France, this stripling from the dim mountain border-land of Austro-Hungary landed on our shores, entirely unknown, and poor in everything save genius and training, and courage...”[4]

To display his growing celebrity, Tesla now moved uptown. For his lodgings, Tesla chose the Gerlach Hotel on 27th Street, between Broadway and Sixth Avenue. Built in 1888 at a cost of one million dollars, the Gerlach was an imposing 11-story fireproof building featuring elevators, electric lights and sumptuous dining rooms.[5]

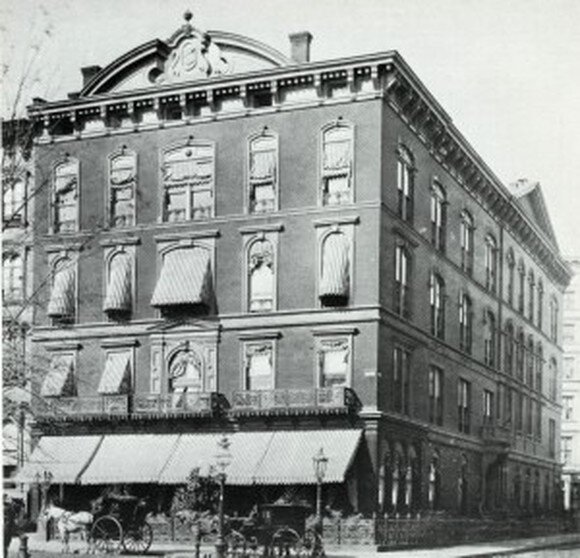

Tesla also began dining at the most fashionable restaurant in Manhattan, Delmonico’s on Madison Square. Delmonico’s chefs had invented signature dishes such as Lobster Newberg, Chicken a la King, and Baked Alaska. But more than the food, Delmonico’s was the hub of New York society, the place to see and be seen.[6] In July 1894, Tesla was interviewed at Delmonico’s by Arthur Brisbane from Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, and Brisbane described him as “almost the tallest, almost the thinnest and certainly the most serious man who goes to Delmonico’s regularly.”[7]

Delmonico's on Madison Square. From http://www.theamericanmenu.com/2010/05/survival-of-fittest.html

The Gerlach Hotel on 27th Street, now known as the Radio Wave Building. Courtesy of AtlasObscura

But the most important location for Tesla was his new laboratory at 33-35 South Fifth Avenue (today LaGuardia Place) where he occupied the fourth floor of a factory building. Located just south of Washington Square, his new laboratory was “in the heart of that picturesque neighborhood known as the French Quarter, teeming with cheap restaurants, wine shops, and weather-beaten tenements.”[8] There, Tesla experimented with wireless lighting, giving demonstrations to friends including the architect Stanford White as well as Mark Twain.

Both White and Twain were members of The Players, a club where actors, writers, and painters mingled with bankers and businessmen, and in 1892, White nominated Tesla to join the group. Located in a Gramercy Park townhouse, The Players became a regular haunt for Tesla.

But just as everything seemed to be going so well for Tesla, tragedy struck. In 1895, a fire gutted his laboratory and Tesla lost everything. “In a single night,” reported the New York Herald,

the fruits of ten years of toil and research were swept away. The web of a thousand wires which at his bidding thrilled with life had been twisted by fire into a tangled skein. Machines, to the perfection of which he gave all that was best of a master mind are now shapeless things, and vessels which contained the results of patient experiment are heaps of pot sherds.

Mark Twain at Tesla’s laboratory, 1893. Tesla is in the background. From T.C. Martin, “Tesla’s Oscillators and Other Inventions,” The Century Magazine, 49:916-33 (April 1895), Fig. 13.

In response to the disaster, Tesla became severely depressed: “Utterly disheartened and broken in spirit, Nicola Tesla, one of the world’s greatest electricians, returned to his rooms in the Gerlach yesterday morning and took to his bed.”[9] A few nights later, Tesla dropped into The Players where he found the usual gathering of actors, musicians, and artists. “With quick and kind sympathy,” noted the Times, the group “immediately organized an impromptu ‘benefit concert’ for his sole gratification, with an aggregation of talent that, had the public only known about it, would have given a substantial endowment for his new laboratory.” [10]

Fortified by his friends and electroshock treatments from his coils, Tesla overcame his depression. In July 1895, he rented a new laboratory at 46 East Houston Street. There he employed

a clerk who attends to visitors, keeps away cranks, keeps a scrapbook, and sees that everybody who has real business with the inventor is provided with the latest copy of some scientific paper until Mr. Tesla is disengaged. He also has a dozen or more mechanics who are as loyal to him as Edison’s men are to him; but . . . the problems he sets for himself to solve do not permit their rendering him the same sort of assistance that the Wizard’s [i.e., Edison’s] men furnish to their employer.[11]

At Houston Street, Tesla investigated x-rays and built a remarkable radio-controlled boat, but his major interest was developing a system for transmitting power around the world without using any wires.

Main room of Tesla’s laboratory at East Houston Street. From http://blog.world-mysteries.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Tesla_fig06.jpg

The Players at 16 Gramercy Park. From http://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.fr/2010/11/players-no-16-gramercy-park.html.

Patent diagram showing Tesla’s radio-controlled boat and transmitter. S is a generator producing electromagnetic waves and is connected to an antenna. To its left is the control box. From NT, “Method of and Apparatus for Controlling Mechanism of Moving Vessels or Vehicles,” US Patent 613,809 (filed 1 July 1898, granted 8 Nov. 1898), Figure 9.

To pursue wireless power, Tesla began experimenting with increasing the power of his transmitter at Houston Street and was soon generating thirty-foot sparks.[12]

“Tesla’s system of electrical power transmission through natural media. — View of model transformer, or “oscillator,” photographed in action. -- Actual width of space traversed by the luminous streamers . . . over sixteen feet. . . . Estimated electrical pressure two and one-half million volts.” From Electrical Review, supplement, 26 Oct. 1898, in TC 13:127. Available at Tesla Wardenclyffe Project Archives, file:///Users/wc4p/Desktop/picture05.htm.

Although Tesla was able to generate such powerful currents at Houston Street, he could not ascertain how these currents propagated through the earth’s crust. This was because the multiple electrical systems in Manhattan—for telegraphy, telephony, lighting, and transportation—produced too much interference. Consequently, Tesla moved for eight months in 1899 to Colorado Springs where he built a large magnifying transmitter and sent enough current through the earth to illuminate light bulbs a mile away.

Satisfied with these results, Tesla returned triumphantly to New York and to new rooms in the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. He also began courting investors for his wireless power scheme, and met with J.P. Morgan in his library in his home at 36th and Madison Avenue.

Morgan's library in his home on 36th Street where he met with Tesla. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/service/pnp/agc/7a17000/7a17800/7a17899r.jpg

Morgan invested $150,000 in Tesla’s wireless power scheme, and Tesla built a power station at Wardenclyffe, near Shoreham, on Long Island. Tesla turned to Stanford White to design the building and 187-foot tower. Beneath the tower, Tesla sank a 120-foot well so that he could pump electrical energy into the earth that he believed would travel to the other side of the planet.

Colorized photograph of Tesla's Laboratory and tower at Wardenclyffe, Long Island. From http://www.fanpop.com/clubs/nikola-tesla/images/26914499/title/wardenclyffe-tower-1903-stanford-white-photo

However, just as Tesla was putting the final touches on the tower, Guglielmo Marconi beat him to the punch. In December 1901, Marconi announced that a signal had been transmitted from England to Newfoundland. Marconi, not Tesla, was the new wunderkind of radio.

In response, Tesla proposed to Morgan that they manufacture receivers “no bigger than a watch” that could receive news, telephone messages, and telegrams from Wardenclyffe, but the financier refused to invest any more money. Meanwhile, Tesla discovered how difficult it was to pump oscillating currents into the earth. Distressed that he could not square physical reality with what he could see so clearly in his mind, Tesla suffered a nervous breakdown in 1905.

Over the next 35 years, Tesla worked on several more inventions, including a compact bladeless steam turbine that he hoped would be used in airplanes and automobiles. To attract investors, Tesla maintained offices first in the Metropolitan Life Tower and then the Woolworth Building, each of which at the time was the tallest building in Manhattan. As his fortunes declined, Tesla was moved to modest offices at 8 West 40th Street. Since he often fed the pigeons in nearby Bryant Park, the City has designated one corner of the park as “Nikola Tesla Corner.”

http://www.teslasociety.com/pictures/tesla_corner/corner_1.jpg

Throughout his life in Manhattan, Tesla lived in hotels, and in the thirties, he was forced to move from one hotel to another when he could no longer pay his bills. He eventually wound up at the Hotel New Yorker, where staff described him as having “a vigorous temperament and emphatic ideas about personal health” which included keeping everyone at least three feet away to avoid their germs.[13]

Hotel New Yorker. http://www.allabouttesla.com/teslablog/wp-content/uploads/2009/04/new-york-3.jpg

Rather than germs, though, it was a taxi that ultimately laid Tesla low. In 1937, while taking his daily walk around his beloved city, a cab hit him. Tesla refused medical treatment for his injuries and he never fully recovered. He died in his sleep on January 7, 1943, and his funeral took place at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York.

Tesla's Funeral at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, 1943. http://picturesofinfinity.files.wordpress.com/2011/12/nikola-tesla-funeral.png

From beginning to end, New York was the stage on which Tesla acted out his career—his dramatic ascent from penniless immigrant to celebrated electrical savant and his painful fall from fame to obscurity. Tesla’s life was, truly, a New York story.

Bernie Carlson is Professor and Chair of the Engineering and Society Department at the University of Virginia. A historian of technology and business, he has published widely on invention and entrepreneurship, and his newest book Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age, has just been published by Princeton University Press.

[1] Nikola Tesla, My Inventions: The Autobiography of Nikola Tesla, ed. B. Johnston (Williston, Vt: Hart Brothers, 1982), 71.

[2] Nikola Tesla, Testimony in Complaint’s Record on Final Hearing, Vol. 1: Testimony, Westinghouse vs. Mutual Life Insurance Co. and H.C. Mandeville [1903], Item NT 77, Nikola Tesla Museum, Belgrade Serbia, 195. Hereafter cited as NT Motor Testimony.

[3] William B. Nellis testimony; NT Motor Testimony, 122-3 and 132.

[4] Joseph Wetzler, “Electric Lamps Fed from Space, and Flames that Do Not Consume” Harper’s Weekly, 35 (11 July 1891): 524 in Iwona Vujovic, comp., The Tesla Collection: A 23 Volume Full Text Periodical/Newspaper Bibliography (New York: Tesla Project, 1998), 3:104-106. Hereafter cited as TC.

[5] “Mr. and Mrs. Gerlach Assign. Owners of Hotel Unable to Carry Heavy Debts Any Longer,” New York Times, 3 June 1894 and Moses King, King’s Handbook of New York City, 1893 (Boston: Moses King, 1893; reissued New York: Benjamin Blom, 1972), 1:230.

[6] Lately Thomas, Delmonico’s: A Century of Splendor (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1967).

[7] Arthur Brisbane, “Our Foremost Electrician,” New York World, 22 July 1894, in TC 9:44-48.

[8] Walter T. Stephenson, “Nikola Tesla and the Electric Light of the Future,” The Outlook, 9 Mar. 1895, 384-386 in TC 9:116-118.

[9] Both quotes from “Fruits of Genius were Swept away.” New York Herald, 14 March 1895, in TC 9:119.

[10] George Heli Guy, “Tesla, Man and Inventor,” New York Times, 31 March 1895 in TC 9:140-42.

[11] “Nikola Tesla’s Work,” New York Sun, 3 May 1896 in TC 11:64-65.

[12] “Tesla Would Use Air as Conductor,” New York Herald, 27 Oct. 1897 in TC 13:129.

[13] “Nikola Tesla Dies: Prolific Inventor,” New York Times, 8 Jan. 1943.