The Manhattan Street Grid Plan: Misconceptions and Corrections

By Jason M. Barr and Gerard Koeppel

The Manhattan street grid plan of 1811 — both figuratively and literally — defines the city. It has created its identity while prompting continuing debate about whether it’s the “greatest grid” or “one of the worst city plans.”[1] Despite the endless fascination after 200 years and counting, the grid’s history and its effect on Gotham are still not fully understood. We aim to correct the record. Here, we introduce some key misconceptions and their corrections; in eight monthly installments, we will discuss each one in more detail.

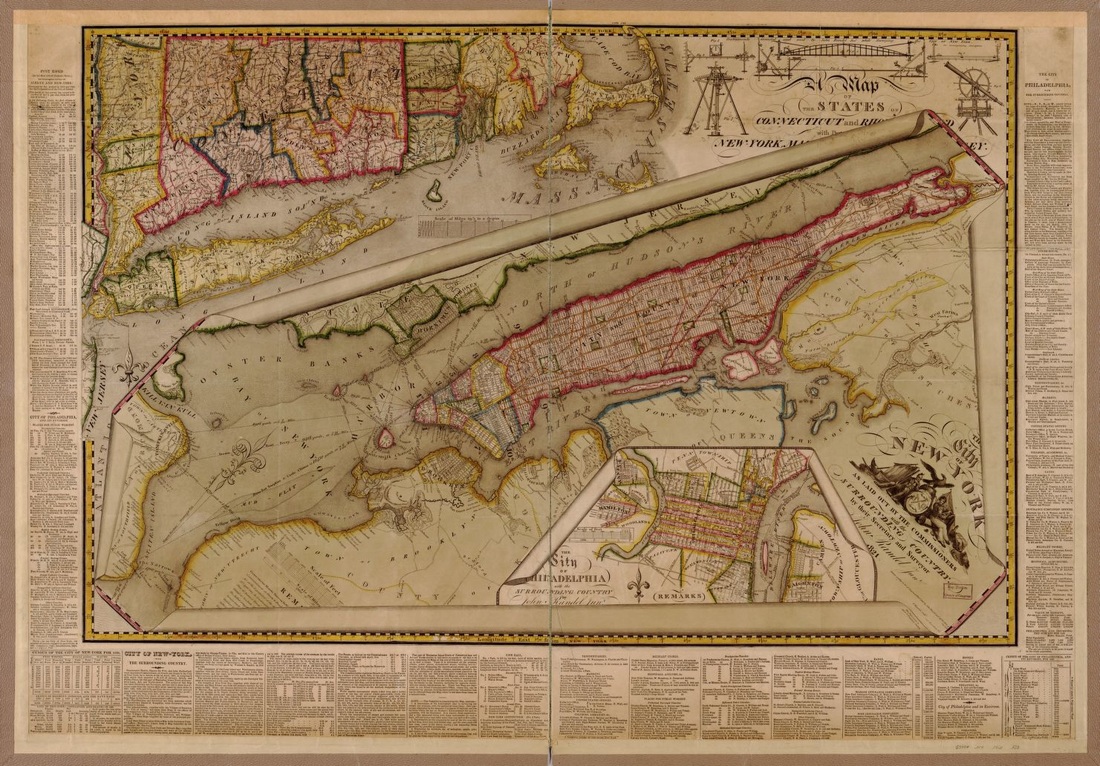

John Randel, The City of New York as laid out by the Commissioners with the surrounding country, Library of Congress Geography and Map Division Washington, D.C.

Myth #1: “Randel’s Matrix”

The conventional wisdom is that the grid plan was created by John Randel, Jr., the chief surveyor for the commission charged with coming up with a future street plan, and who tirelessly trudged through the wilds of Manhattan in order to map it. But the truth is that Randel did not create the plan. While his efforts were Herculean, the plan derived not from Randel’s head, but rather was based directly — and without acknowledgement — on the work of late surveyor, Casimir Goerck, who had mapped out a large central section of rural Manhattan in the 1780s and 1790s. Randel was an employee of the Commissioners; it was they — three venerable, nationally prominent men — who chose to adopt and expand Goerck’s plan; Randel, a barely twenty-year-old Albany provincial, followed their instructions.

Myth #2: The Commissioners as Visionaries

The only record the Commissioners left for posterity was an eleven-page document outlining the basics of the map that gridded Manhattan from North (now Houston) to 155th Streets. The document, dubbed “Explanatory Remarks,” explains little of the Commissioners’thinking. Their personal writings practically ignore their work. Over the generations, great intention has been ascribed to the Commissioners that does not exist. Analysis of the Commissioners’ actions shows that the grid plan was not a “plan” so much as a convenience to satisfy a deadline. That is, not a plan but rather a “rush job” because the Commissioners demonstrated little interest in their responsibilities until the final months of their four-year term. Manhattan’s future was sealed with scarcely a discussion.

John Randel, Jr., A Map of the city of New York by the commissioners appointed by an act of the legislature passed April 3rd 1807 (known as the Commissioners’ Plan), 1811; 106 x 30 7/16 in.

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

Myth #3: Aaron Burr

When it comes to Aaron Burr and his role in the history of New York City (as opposed to the nation), the best known story is that he created the Manhattan Company in 1799 to supply the city with much-needed fresh water, but used most of the money the company generated for his prime and secret purpose, to start a bank that is now JPMorganChase. The company’s notorious neglect of its monopoly water responsibilities subjected New Yorkers to four decades of fire and disease before the city completed its pioneering Croton Aqueduct, the first piece in New York’s now vast and iconic modern water supply. Little known is the pivotal role Burr played in events that led directly to the street commission that gave Manhattan its grid.

Myth #4: The Grid Plan Created Manhattan’s Small Lots

It is a general assumption that Manhattan’s standard lot size of 25’ x 100’ was part of the 1811 grid plan. This is not true. Like many details that were omitted, it said nothing about lot size. In fact, the 25 x 100 lot long predated the grid plan. Standardization in lot size began during the Dutch colonial period and continued into the nineteenth century. 25’ x 100’ was found to be a size both most suitable for living and working in a small merchant town and at the limits of building technology. The tradition remained as the grid plan was implemented, especially as its 200’ blocks were conducive to two rows of 100’ lots.

Myth #5: The Grid Plan Leveled Manhattan

Images abound of small wooden houses perched atop lonely hills along 5th Avenue, as new roads obliterated natural Manhattan to make way for the grid. This has left the impression that Manhattan was flattened by the grid plan. But the truth is a bit subtler. Rather, implementation in practice was more of a “smoothing" than a leveling. North of 14th street was a jagged stretch of hills and valleys; the former came down, the latter went up. The general elevation, though, remains the same as it was 400 years ago.

Myth #6: The Grid Plan Caused Too Much Density and Rampant Land Speculation

The grid plan in the nineteenth century became a symbol of the evils of hyper-dense, unsanitary living because critics argued that it encouraged poor urban health. However, as compared to the short and narrow blocks south of Houston Street, the larger blocks of the plan, may have, in fact, helped reduce population density. Another trope is that once the plan was set, greedy land speculators went on a tear — driving prices up. But this is like blaming the automobile for traffic congestion; land price bubbles are a problem of human psychology, not maps.

Myth # 7: Static Manhattan, Part I

While it is true that the plan has forever set a rectangular city, it has demonstrated a large degree of flexibility and change over the years, and is not static like many believe. For example, Lexington and Madison Avenues, and Central Park were all added after the plan was first established. More broadly, a comparison of Manhattan from 1900 to the present shows a surprising evolution in block configurations.

Myth #8: Static Manhattan, Part II

When the Dutch first settled Manhattan, they began to fill in the shorelines. In fits and starts, Manhattan has been growing ever since. Today we tend to see Manhattan as a fixed island, but over the centuries it has changed its size to a considerable degree. Visions for its continued expansion have been proffered throughout the centuries; the future growth of the city may require implementing some of these visions and offer competing alternatives to the plan.

In the next installment, we turn to Myth #1, and how the grid plan really came to be….

Jason M. Barr is Professor of Economics at Rutgers University-Newark, and the author most recently of Building the Skyline: The Birth and Growth of Manhattan’s Skyscrapers. Gerard Koeppel is the author of City on a Grid: How New York Became New York, Water for Gotham: A History, and Bond of Union: Building the Erie Canal and the American Empire.

[1] Hilary Ballon, ed., The Greatest Grid: The Master Plan of Manhattan, 1811-2011 (Columbia University Press, 2012); Peter Marcuse “The Grid as City Plan: New York and Laissez-Faire Planning in the Nineteenth Century,” Planning Perspectives 2 (1987): 287-310.

Series Expansion

By Gergely Baics and Leah Meisterlin

Myth #9: A System of Block and Lot Divisions

The grid is often understood as a foundational system of land subdivision and cadastral allotment. Accordingly, it divides Manhattan into a highly regularized system of rectangular blocks, subdivided into lots, making standard units of real estate available for development. Previous posts (#4 and #6) have addressed two myths following from this line of reasoning, specifically the extent to which block sizes determined lot sizes, and how the relentless regularity of blocks and lots contributed to rampant real estate speculation. Less recognized though equally important is an inverse understanding of the grid, one that emphasizes connectivity. Our recent research discusses how the Manhattan grid provides a regular, predictable, and variable network of connections and accessibility between the city’s spaces. Conceptually, this entails more than just shifting attention from the rectangular blocks to the rectilinear streets. It involves rendering visible the grid’s underlying logic as a nodal network of highly regularized and hierarchical intersections.

Myth #10: Example of Laissez-Faire Planning

The 1811 Commissioners’ Plan had nothing to say about which activities should take place where in the city, contributing to the widely held view that it was an example of laissez-faire master planning. This is ahistorical, because the plan’s reliance on real estate actors to populate new lots and blocks with buildings as they saw fit not only reflected the commissioners’ faith in capitalist property markets, but also their lack of a conceptual framework for distinct land uses. It is also somewhat inaccurate, because the plan inadvertently encoded the city’s first algorithm for land use. Specifically, the grid’s peculiar geometry, described in our previous post (#9), produced a regularized but differential topology of connectivity and accessibility. Activities that depend on high levels of access, like commerce and trade, would likely occupy more accessible avenue locations despite those commanding higher rents. In contrast, residential and especially industrial uses, less reliant upon pedestrian traffic, would likely be satisfied with less accessible cross-street lots. Taken together, the result is a set of land-use incentives that might be described as "zoning before zoning."